Why peaceful demonstrations in Uganda often end in chaos

This entrenched cycle has fueled a complicated relationship between citizens and authorities, with each side citing different reasons for the tension.

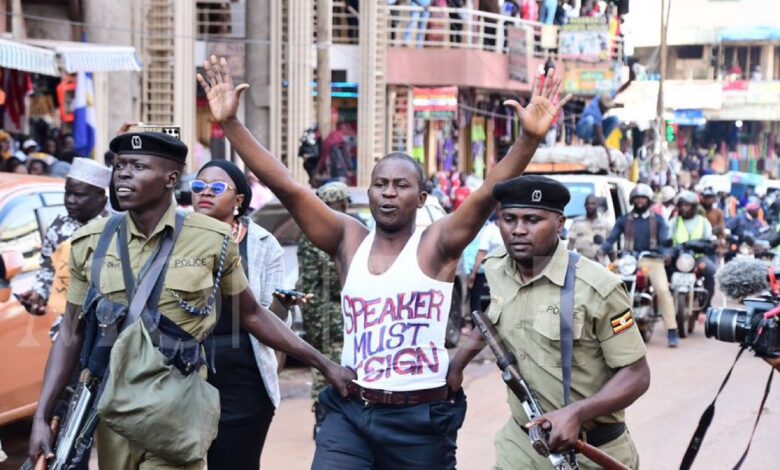

In Uganda, public demonstrations rarely follow the peaceful scripts activists hope for. Even with organizers emphasizing peaceful intentions, scenes of tear gas, arrests, and confrontations with police often tell a different story. But why do demonstrations in Uganda so often turn tense and chaotic?

Despite the constitutional right to assemble peacefully, Ugandans have repeatedly witnessed peaceful demonstrations escalate into clashes, with law enforcement typically citing security concerns as the reason.

This entrenched cycle has fueled a complicated relationship between citizens and authorities, with each side citing different reasons for the tension.

One recent example stands out: a gathering intended to raise awareness about climate change. Young activists, holding banners and chanting slogans, assembled on Kampala’s streets. Within minutes, police arrived, dispersing the group with batons and issuing warnings about “unlawful assembly.”

“We were here peacefully, but they approached us like we were criminals,” said Grace Ainebyoona, one of the organizers. “It’s hard to imagine a protest that could stay peaceful with that kind of response.”

This response is familiar to activists, who say it’s emblematic of Uganda’s restrictive approach to public protests. According to Dr. Michael Kamya, a political scientist specializing in East African governance, “There’s an underlying belief that protests are inherently destabilizing. Law enforcement agencies have been conditioned to see them as security threats, rather than a form of democratic expression.”

Critics, however, argue that the police’s heavy-handed approach often creates the very chaos it seeks to avoid. “When protests are disrupted so aggressively, tensions rise,” says Agnes Tumusiime, a local human rights advocate. She highlights that for many Ugandans, the sight of riot police at a protest signifies a likelihood of escalation rather than security.

Uganda’s Public Order Management Act (POMA) grants police broad powers over public gatherings, a law that activists say is used selectively to suppress dissent. Demonstrations must receive police approval, and while some are granted permits, those with perceived political or social criticism often find themselves denied permission.

“This selective allowance fosters a tense atmosphere,” Dr. Kamya explains. “When certain groups are denied a voice, frustration mounts, and people feel pushed to demonstrate in defiance.”

After witnessing several protests turn chaotic, some Ugandans are increasingly wary of participating. A survey by the Uganda Institute of Policy Studies found that nearly 60% of respondents believed public demonstrations were “too risky” given the likelihood of police interference.

“I want to support causes I care about, but the risk is just too high,” says John Okurut, a university student who once demonstrated for electoral reform. “When you know there’s a high chance of getting hurt or arrested, you think twice about attending.”

While the standoff between citizens and authorities persists, many are advocating for a new approach that respects citizens’ rights while maintaining public order. “We need dialogue, better training for law enforcement, and policies that see protest as a healthy part of democracy,” says Tumusiime.

For now, the future of peaceful protest in Uganda remains uncertain. The gap between citizen expression and governmental control has widened, leaving the right to protest in a delicate balance. As Ugandans watch other democracies uphold the freedom of assembly, the desire to achieve a safer, more open platform for protest is stronger than ever—but the road ahead is still fraught with obstacles.