Is Uganda’s sliding into political cultism as Winnie Byanyima is supposing?

Critics argue that such symbolism undermines the fabric of Uganda’s multi-ethnic and multi-party democracy. In a nation with over 50 tribes and a complex political landscape, public leaders are expected to embody unity not personalize power.

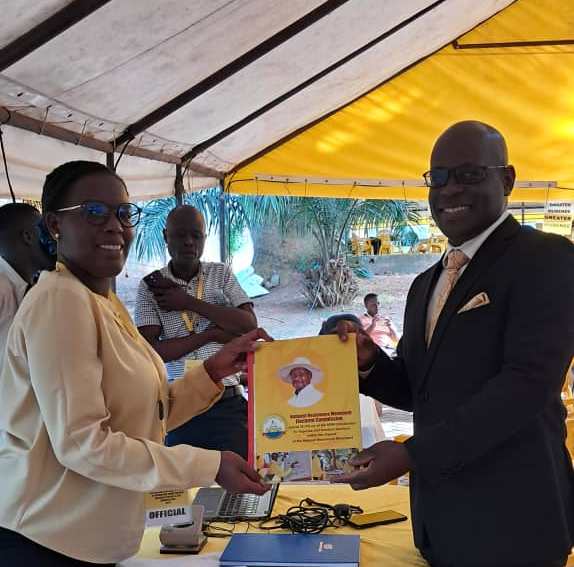

When Vice President Jessica Alupo and Speaker Anita Among appeared draped in Banyankore traditional attire paired with the ruling NRM’s signature yellow at a public function, it may have seemed like a harmless nod to cultural pride and party identity.

But for UNAIDS Executive Director Winnie Byanyima, the spectacle wasn’t just about fashion, it was a flashing red light warning Uganda about the creeping dangers of political cultism.

Byanyima, herself a former legislator and a staunch advocate for democracy and human rights, took to X (formerly Twitter) with a sharp critique, “This wasn’t about celebrating Banyankore culture. It was about enacting obedience to President Museveni… That’s not cultural appreciation, it’s political theatre. And it’s dangerous.”

Her comments have sparked a fierce debate across Uganda’s political and civic spaces. At the heart of her argument is a concern that loyalty to President Museveni, who has ruled Uganda since 1986, is increasingly becoming a litmus test for political survival, eclipsing allegiance to democratic institutions, the constitution, or the diverse people of Uganda.

Dr. Sarah Arinda political a analyst, agrees with Byanyima’s assessment. “When top leaders perform visible acts of loyalty that mimic ethnic and partisan identity, it erodes the neutrality expected of public institutions. It breeds exclusion and a silent fear among those who do not conform,” she says.

Byanyima further pointed out that neither Alupo nor Among is ethnically Munyankore, and that their choice to don the attire of the President’s tribe was not coincidental. “It was a staged show of devotion to Museveni,” she wrote. “When leaders dress in the symbols of one man’s heritage and party, they send a clear message: ‘We are with him, not necessarily with the people.’”

Critics argue that such symbolism undermines the fabric of Uganda’s multi-ethnic and multi-party democracy. In a nation with over 50 tribes and a complex political landscape, public leaders are expected to embody unity not personalize power.

Byanyima’s message is a civic alarm bell, that the real threat to Uganda’s democracy isn’t in the fabric worn by its leaders but in the message it sews into the national conscience, that political power flows not from the people, but from performative loyalty to one man.

“This is how personality cults work,” she warned. “Institutions weaken. Parties become tools of one person. Public officials act as loyalists, not guardians of the public interest. The state becomes personal.”

Whether Byanyima’s post was a bold civic act or an uncomfortable truth remains to be seen, but one thing is clear, Uganda must decide whether its leaders will continue to dress for power, or act in service of the people.