Justice delayed or justice served? Inside Uganda’s remand and bail System

According to the Uganda Prisons Service, over 50% of the prison population consists of pretrial detainees, many of whom wait years before their cases are heard.

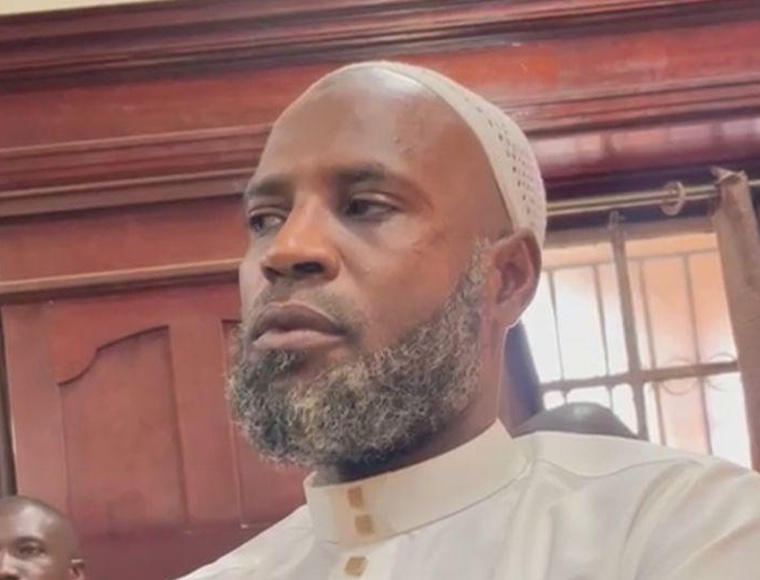

The High Court in Kampala has today granted Shs 2 million cash bail to Hajj Ali Mwizerwa, a man who had been on remand for several months on charges of allegedly defiling his 14-year-old stepdaughter.

His release has sparked public debate, once again shedding light on Uganda’s legal system and its handling of suspects awaiting trial for serious offenses.

For Hajj Mwizerwa, like thousands of others in Uganda’s overcrowded prisons, bail represents a long-awaited reprieve from months of uncertainty behind bars. But for victims and their families, such decisions often feel like a denial of justice. Uganda’s remand population remains alarmingly high, with suspects of violent crimes languishing in jail for extended periods due to case backlogs and limited judicial resources.

According to the Uganda Prisons Service, over 50% of the prison population consists of pretrial detainees, many of whom wait years before their cases are heard. Critics argue that the prolonged detention of suspects often without a conviction violates their fundamental rights and undermines the principle of “innocent until proven guilty.”

Human rights lawyer Sarah Kiyingi noted that bail, while a constitutional right, is often a contentious issue. “The release of suspects in cases involving sexual violence, such as defilement, ignites public outrage and raises questions about the safety of victims and witnesses. Many believe that suspects should remain in custody until a verdict is reached, especially in cases that involve vulnerable victims.”

However, she quickly emphasized that bail is not an acquittal but a temporary release to ensure that suspects can adequately prepare their defense.

“Denying bail without just cause violates the accused’s right to personal liberty. But the courts must also ensure that victims feel protected and that justice is seen to be done.” She added.

Kiyingi further explains that the delays in Uganda’s judicial process often stem from systemic issues: understaffed courts, limited resources, and corruption. The average time a suspect spends on remand for capital offenses like defilement can exceed two years, far beyond the legally recommended six months.

Such delays, according to her, erode public trust in the justice system and, in some cases, lead to mob justice or vigilante actions.

“Judicial reforms, including digitizing court processes and increasing the number of judges, have been proposed to address these challenges. But progress remains slow.”

Activists and legal analysts agree that Uganda’s remand and bail practices require urgent attention. Balancing the rights of suspects with the need to protect victims and maintain public safety is a delicate task, but it is essential for the integrity of the judicial system.

As Hajj Mwizerwa adjusts to life outside prison walls, his case serves as a stark reminder of the broader issues facing Uganda’s justice system. The question remains: Will justice be served, or will it continue to be delayed?